Pain and grief and shock explode from the pages of Lamentations. The unthinkable has happened: Jerusalem has fallen.

The year is 586 BCE. A year-and-a-half long siege by the Babylonian empire has recently ended with their army sweeping through the city of Jerusalem in a mighty flood of fire and sword. Every building burns. The city's walls have been torn down and the temple lies in ruins. Dead bodies burn in the streets and jackals prowl the empty market squares. Survivors were dragged off to become slaves of the empire or now starve in the broken city.

Lamentations is a set of five poems (or lyrics) that were originally sung by survivors to mourn the destruction of Jerusalem. Instead of blaming the invading Babylonians, these singers unanimously view the violence they've suffered as if God himself had held the sword.

Very few parts of the Bible give space to the survivors of God's violence to speak out. Therefore, their lament holds a unique power to convict us of the harmful way we read not just Lamentations, but the whole Bible.

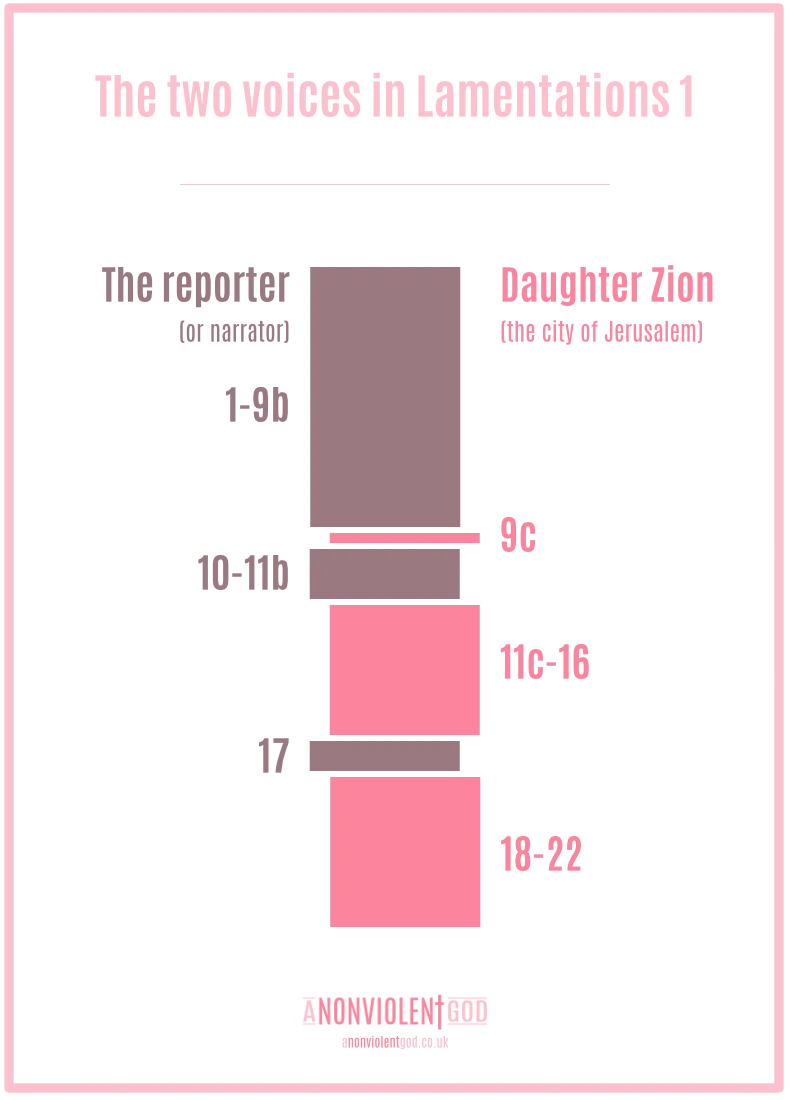

There are two voices in Lamentations 1

The poetic form of Lamentations makes it hard to identify who is speaking (or rather singing), especially if you are unfamiliar with the book.

In the first poem, there are two voices who sing three times each in a call-and-response format.

The first voice acts like a modern-day television news reporter—if news reporters sang! Imagine him looking into a video camera dispassionately narrating the facts while the smoking shell of a war-torn city lies behind him. We'll call him the reporter.

The second voice is that of the city of Jerusalem. Her words were most likely composed by a female survivor who prophetically gives her city a personality and a voice in order to challenge the prevailing religious narrative. The reporter calls her Daughter Zion or simply Zion or Jerusalem, though she calls herself Daughter Judah at one point (15c). She represents both the people of Jerusalem and the larger nation of Judah as a whole.

The reporter's perspective

The first verse of the book summarises the complete upheaval of Daughter Zion’s world. From full of people to deserted, from great to insignificant, from queen to slave, everything has changed for her.

How deserted lies the city,

once so full of people!

How like a widow is she,

who once was great among the nations!

She who was queen among the provinces

has now become a slave.

— Lamentations 1:1 NIV

The reporter hints at the reason for this dramatic turnaround when he compares her to a widow in verse 1b. God’s covenantal relationship with Isreal is often thought of as a marriage (e.g., Jer. 31:32) so the only way she can be “like a widow” is if God has left her.

Something terrible has occurred between God and Daughter Zion.

In verse 2, the reporter leads us to believe this separation may have been Daughter Zion's fault. He tells us how "she weeps at night" (2a), yet she goes uncomforted despite "all her lovers" (2b).

By verse 5, it's clear the reporter is not an impartial observer of her tragedy. He bluntly states how the ransacking of this once great city is God's punishment of her "many sins" (5b).

For the LORD has punished Jerusalem

for her many sins.

— Lamentations 1:5b NLT

He believes she has cheated on God

In verse 8, the reporter escalates his "lovers" comment from verse 2 into a full-blown accusation of infidelity. Everyone has "seen her naked" (8b).

Jerusalem has sinned greatly

and so has become unclean.

All who honoured her despise her,

for they have all seen her naked;

she herself groans

and turns away.

Her filthiness clung to her skirts;

she did not consider her future.

— Lamentations 1:8-9a NIV

He thinks her naïve. How could she not have considered the consequences of her actions? What did she think God was going to do to her if she cheated on him multiple times?

Throughout this first poem, the reporter draws our attention to her lovers (2b), her sins (5b), her nakedness (8b), her filthiness (9a), and her fall (9b).

He’s unsurprised by what’s occurred. So much so, that despite noticing how she weeps bitterly at night (1:2a) without someone to comfort her (1:2b as well as 9b), her tears illicit no empathy from him.

We find ourselves agreeing with him

It’s clear the reporter views the city’s fall as all her fault. And as we read his version of the story, we find nothing unexpected about what he says. Of course, Jerusalem’s destruction was a consequence of sin, we think.

It all matches up with how other parts of the Old Testament explain Jerusalem’s ruin as the consequence of God’s anger at his people’s disobedience (e.g., 2 Kgs. 24:20 and 2 Chr. 36:16). Deuteronomy 28 even foretells both the city’s fate and the people’s enslavement if the people sin against God.

We nod along as the reporter informs us how Daughter Zion “has sinned greatly” (1:8a) and reports on the aftermath of her betrayals.

However, this isn't the only reason we agree with him.

"By speaking first, [the reporter] convinces us to accept his perspective on Zion's suffering. He thinks she brought it upon herself."

— Kathleen M. O'Connor

Lamentations and the Tears of the World, p.17

The male reporter speaks first, so it’s his voice we take as gospel. We add extra credence to his viewpoint because he laments without emotion and in a factual manner that we still associate with authority and truth. After only eight verses and change, we find ourselves thinking, If only she had made better life decisions, she could have averted this tragedy.

We accept his version of events before the emotional Daughter Zion even gets to speak.

And this is where Lamentations highlights the harmful way we read the Bible.

We agree with the reporter and blame the victim.

We side with the man and blame the woman.

Daughter Zion interrupts

The reporter is in full flow when Daughter Zion unexpectedly interrupts him in verse 9. All she sings is a single line.

"Look, LORD, on my affliction,

for the enemy has triumphed."

— Lamentations 1:9c NIV

Look, Lord.

Every time she responds in this first poem, she asks for the same thing: someone to witness her suffering.

This desire is alien to many of us. Our western culture influences us to keep our pain and grief private—so much so that our funerals are often stoic affairs. The last thing we want are witnesses to our vulnerability, yet Daughter Zion is desperate for one.

The reporter ignores her

The reporter sees her, but he continues as if no one interrupted him. He doesn’t even acknowledge that she’s spoken. Yet it’s clear he’s heard her cry for his next words twist the idea of comfort. Instead of laying on hands to comfort her or stretching out arms to embrace her, he talks about what the enemy’s hands got up to.

The enemy laid hands

on all her treasures;

she saw pagan nations

enter her sanctuary—

those you had forbidden

to enter your assembly.

— Lamentations 1:10 NIV

On the surface, it appears as if the reporter is talking about the temple but, given the personification of the city of Jerusalem as a woman, hands touching “her treasures” and foreigners entering “her sanctuary” also act as sexual innuendos regarding her betrayals.

When you think someone’s suffering is their own fault, don’t you find it that much harder to comfort them?

It’s the same for the reporter. His judgement that Daughter Zion’s only got herself to blame means he hardens his heart and ignores her cry for a witness. He makes no move to comfort her.

Daughter Zion interrupts again

Daughter Zion's second interruption is her longest speech in Lamentations 1. From her perspective, things are not as obvious as the reporter is stating, and she makes her side of the story known.

She expresses her version of events clearest in verse 15c. Here, she resorts to third-person and speaks with the tone of the reporter to convey her message.

In his winepress the Lord has trampled

Virgin Daughter Judah.

— Lamentations 1:15c NIV

If the reporter is to be believed, Daughter Zion has betrayed God with many lovers.

If Daughter Zion is to be believed, God has punished a virgin and not a whore in his trampling of the city.

Whose version do we believe?

Lamentations doesn't offer us the clear-cut story of sin and God's punishment we were perhaps expecting it to. Instead, it challenges our traditional understanding of God's violence by asking us to pick sides.

Do we side with the perpetrator by excusing God's violence (perhaps by naming it as justice), by ignoring the violence of the invading empire (here, the Babylonians), and by blaming the victims for Jerusalem's fall (in this case, the people of Jerusalem)?

Or do we side with the victims (Daughter Zion and the people she poetically represents) as they "groan" and "search for bread" (11a)?

In any context other than our Holy Bible, we would conclude that a victim is never to blame for the violence they've suffered. We would say that the people of Jerusalem are not to blame here, in the same way that the people of Ukraine today are not to blame for the atrocities committed on them by Russia.

And yet, by sticking to a narrative that says God is punishing his people's disobedience through Jerusalem's destruction, we're blaming the victims. We're blaming the dead, the starving, the homeless, the widowed, the orphaned, and the enslaved for the violence perpetrated against them by the invading Babylonian army.

How can we accept this?

This is a harmful way to read Lamentations and, indeed, the whole Bible. If we accept the viewpoint that victims are responsible in Scripture for their own victimisation, then this will invariably bleed into our modern world. It will cause us to blame victims while letting the perpetrators who harmed them off the hook.

And, like we do in Lamentations, we’ll also find ourselves siding with the man’s version of events over than the woman’s.

Is this really about men and women?

Not convinced by my last sentence?

Let me break it down for you.

The leaders of Judah and Jerusalem were all men.

The leaders of Babylon were all men.

The invading army were all men.

Yet somehow it’s the woman in the story, Daughter Zion, who conveniently gets blamed for the sinful choices and actions of these male leaders.